One of my priorities in how I GM is that I want the players to be active and engaged, not just act as my audience. So when I started planning out a new adventure with a heavy investigation component, I gave serious thought to increasing player engagement.

In the parts of the investigation where they can use their social skills, player engagement is easy. The players interact with villagers to get information. Traditional role playing techniques work well because the players can drive the interactions and role playing happens pretty naturally. All I had to do was prepare enough to know who the villages were and what they knew.

But the traditional techniques don’t serve as well is in the physical side of the investigation – finding clues, examining physical evidence, and then analyzing the findings. The usual problem is that the clue isn’t physically there to be found, so it devolves into a skill check with the GM giving a verbal description of what they find. And the verbal description may be great, but for the player, it’s passive. They listen to the description and either passively accept it or parrot it to the other players who have just heard the GM say the clue.

For me, that’s no bueno. Or, as my old marketing-trained boss would tell me, there was a great opportunity for improvement! Value-added, even.

Preparing Clue Tear Sheets

So I tried something new – made tear sheets for each physical clue they could possibly find or analyze.

In case you’ve not familiar with the term, a tear sheet is a page where the paper is cut so that strips of it are easily torn out. A lot of times you’ll see flyers as tear sheets, with the bottom having little tear-off phone number strips. I did that except instead of phone numbers, I had clues that the players could gain. Here’s the process if you want to do something similar:

- Brainstorm possible investigation activities. Start by determining everything the players could possibly examine and gain information from. I combined some of them, so that, for example, examining the tracks in all the murder sites were all grouped into the same skill check. I didn’t include any social investigation clues, because those naturally lend themselves to roleplaying, plus it’s hard to predict just what a player will ask. I stuck to things they could find with their physical or magical senses and knowledge checks they could make about the evidence they found.

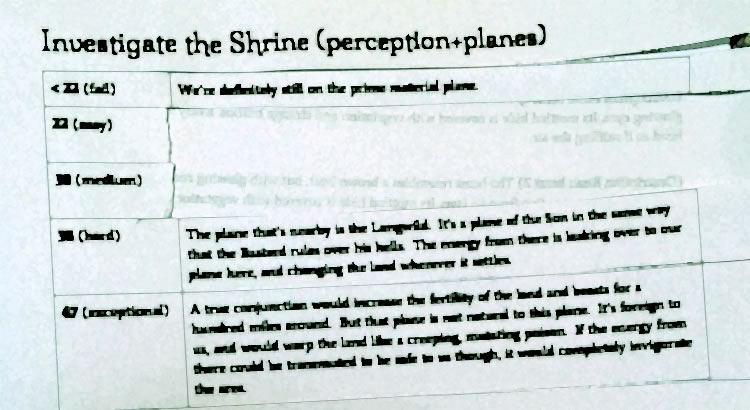

- Organize checks into clue tables. Then I created tables for each investigative activity with clues arranged by threshold values. Here’s the Runebeast Investigation Tearsheet, a pdf of all the clues I made for that investigation. Note, I use a homebrew system, so the exact numbers and skills will be different in your system, but if you have a skill system, this technique should transfer.

- Set values and write up clues. I never just have a pass/fail threshold. Instead I like to have fail/easy/medium/hard/exceptional DCs so I can set the fail number relatively low and still show a difference between a player who rolls okay and a player who rolls a godlike number. For each threshold, I wrote up a clue. Keep in mind that if there is any information that the players need to have, you need to provide it in different ways. You don’t want to investigation to entirely fail if they miss a single bit of evidence. Don’t have investigative choke points like that. Build the players multiple paths to success.

- Cut into Tear sheets. Make sure you only cut up to the edge of the clue and not the DC – that’s for GMs to know only.

Playing with Clue Tear Sheets

So then during the session, it worked like this:

- Players declare their actions. The players say or role play what sort of activity they’re doing (examining the murder site for physical clues, seeing where the tracks lead, trying to see if they can read the ancient rune, etc.). and I tell them what sort of check that represents. They roll it and tell me the number. So far, it works just like normal skills.

- Tear out the clues. I tear out all the clues that are at or below the threshold. So if they roll a 40 (38 is the “hard” threshold), they get the hard, medium, and easy clues. But if they roll a 25, they only get the easy clue. If they fail, they get the “fail” clue, and I had fun coming up with those.

- Hand the clues to players. I made sure to keep my mouth shut when I handed clues to the players who rolled. The player rolls reads the clue and is responsible for role playing/conveying that information to the other players. The GM fades into the background as a mechanical assistant and the player becomes the active agent in the scene.

- Group checks. I allowed assists rather than have everyone roll separately. So if someone wants to do a check (find tracks, feel for magical energies, examine the crypt, analyze the runes, whatever), other people can help them. If the helpers make at least medium check, the main roller can add a +1 bonus to his or her check. If the main roller rolls high enough to earn more than one clue, I gave the easy clue to the helper first for them to act out, and the harder clue to the main roller to act out next. It helped spread the clues around a bit and helped with the role playing, because they can roleplay a watson/sherlock dynamic or two colleagues bouncing ideas off each other or whatever was relevant.

- Rerolls. I used my discretion on rerolls. When they examined multiple murder scenes, I let them roll to glean new clues from the each murder scene, but I didn’t let them spend extra hours on the same scene to find more clues. YMMV.

Post-game analysis

It took some preparation on my part, but wow, it worked great. And honestly, putting together the clues like that really helped me think through how the investigation would work. It was time well spent just as a understand-your-adventure technique.

But the real success was how it played out in session.

The players hoarded the little paper strips with a reverence usually reserved for high-level loot, and were seriously invested in solving the mystery. The players with skills in knowledge or perception got to be the ones role playing to the hilt for a change, not just the social skills folks. I mean, they always got the chance to act out what they were planning to do, but this was a breakthrough in having them really act out what happens after the skill check. They weren’t just sitting back and listening to me give them information.

One funny side effect was that normally the druid and the ranger played reserved characters who didn’t always like to speak much. So the other players would see them read their clues silently and then only say a couple words in explanation. I forget which of them started doing that first. The other players knew that there was info on the clues that wasn’t shared, but their characters didn’t know that, so there was some amusing frustration in the metagame. The druid and ranger didn’t keep anything vital away from the rest of the party, just messed with their minds a bit.

The investigation played out over a couple sessions, so I think it also helped them keep track of what they had discovered from one session to the next. They had that written record of what they knew, and could refer to it if there was a disagreement. And the person who “discovered” the clue was the expert who could remind everyone exactly what the clue said or meant.

Plus, I told them to keep the clues because they’d come in handy.

Later in the story, they needed to convince the villagers to let them take the corpse of a newly-dead villager down to the local shrine to do an experimental ancient heathen ritual. I made the town hall over the subject into a skill challenge, and let them exchange clue strips for +1 bonuses for checks to influence the villagers. In terms of role playing, the strips of paper represented solid evidence in their arguments, so the more evidence they had, the more convincing they sounded.

If you’re interested in running an investigation in your game, I made a blank tear sheet pdf in case you want to print out your won. Free to download, and let me know how it goes.

This looks really helpful! I’ll make sure to use this next Sunday. Thanks!

As a player in this game, I have to say that the session where we used skill tear sheets was *really* enjoyable. There is just something really satisfying about being rewarded with something tangible as a reward from doing something that would ordinarily feel insubstantial.

Seems like it would be. I guess you could say… I phaelia 😛