I was getting ready for a new adventure recently, and I came across “The Automatic Hound” by James Lafond Sutter in Dungeon Magazine #148. It’s a tidy, low-level module that starts with a town terrorized by a mysterious wild beast and quickly escalates into something more. I liked it and wanted to use it as the basis for my adventure, but I would need to adapt it to fit in my campaign. I expected how much I had to change mechanically — it’s a different system, after all. But I was surprised at how some of the small details were affected by trying to fit them into my setting. And even more surprised when I realized that altering the little details did more for adding to the canon of my world than the big aspects of the adventure.

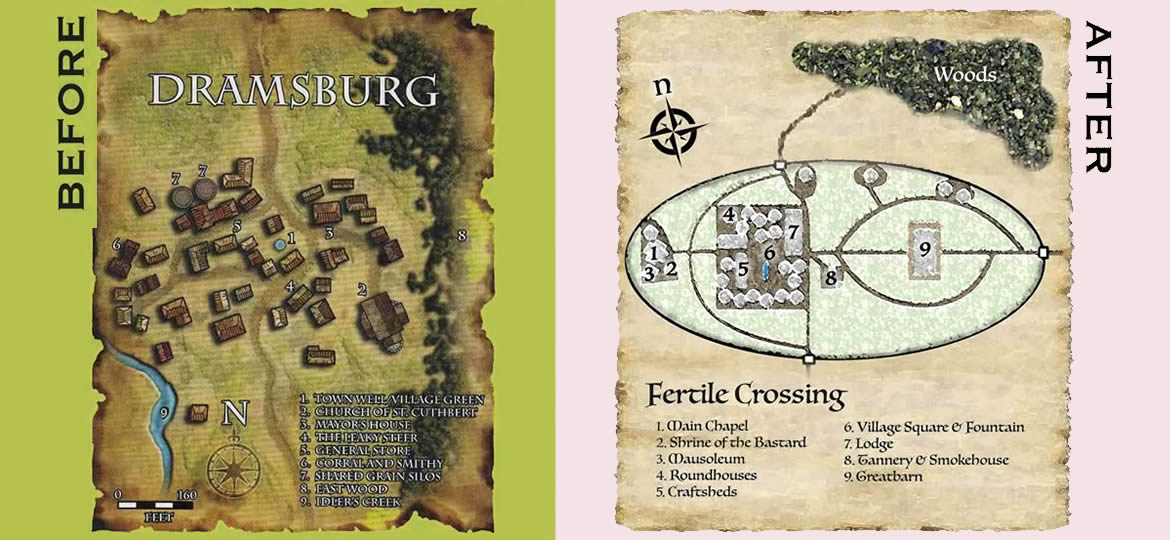

Let me walk you through an example. I started with the low-hanging fruit…changing the name of the town and some characters to fit the flavor of the setting. So Dramsburg becomes Fertile Crossing. I also changed the names of the main character to match my Celtic-inspired culture. Then I got into the descriptive text. As the PCs enter the town in the very beginning of the adventure, Sutter describes it thus:

The town of Dramsburg is quiet as the PCs pass between the outermost houses and into the village proper. Once a bustling community, burbling with the squawks of chickens and the laughter of children, fear has cast a pall over the settlement’s daily activities. Leaves and trash blow lazily through the empty streets and vacant livestock pens. The majority of the villagers peer out at the visitors from between locked shutters, and the few visible’ residents scurry from house to house, hastily completing errands in preparation for nightfall.

But that’s not quite enough.

Something about the description made me think of an old west town with tumbleweeds blowing through. It’s not the impression I want to give, but I couldn’t put my finger on exactly what I thought should be changed. After a few minutes of Googling, I found one of the issues: Iron Age Celtic villages were often built as hill forts, so that if danger threatened, the entire community could hole up securely behind the protection of the walls of the fort.

Okay, that makes sense. Now that I thought about it, I imagined the ancient Celts with their clans were more communal than pioneer America with their focus on independence and that difference would be reflected in their architecture. I made a mental note that villagers in my setting are more communal than I normally think of.

I tried to imagine the scene. There’s my fantasy Celtic-ish village terrified by a ravaging beast, is it going to be empty? No, of course not. Where would all the people and chickens and cows go? They’d gather together in the hill fort where it’s safe. So the first paragraph instead becomes something like this:

Fertile Crossing seems abandoned from a distance, with its outer fields and homesteads empty and quiet. But as you approach the gates of the hill fort, you gain a different impression. The gates are actively manned by several villagers, who scan the horizon as they let you in and then immediately close the gate back up after you enter the fort. It looks like the entire village is stuffed between the walls of the fort, with every bit of the common greens crammed with flocks and herds. The few visible residents scurry from house to house, hastily completing their errands.

But then the next bit we come to a different issue. Sutter writes the following:

Despite their fear, the people of Dramsburg are still hospitable, and parties wishing to purchase supplies at the general store or take their ease in the town’s inn and public house, the Leaky Steer, are quickly ushered inside.

I like the friendly town part, but to me this still sounds too pioneer town and not enough old Celt. To the internet! And a quick trip to Google later suggests they wouldn’t have modern capitalism with general stores and public inns, especially not in my village of about 200 people. Actually, with a place that small, they likely wouldn’t name their buildings, so no Lucky Steer. Mooo.

So I change it to this.

Despite their obvious fear, the villagers are friendly and quickly usher you into the guest lodge.

And we still have a bit of the first paragraph to go. Sutter continues thus:

Rumors regarding the recent troubles are on the tip of every tongue, and the townsfolk are eager to divulge what little they know of the attacks. Within minutes of the PCs’ arrival, however, the town sheriff enters with the mayor, both men looking rumpled and tired.

I’m not feeling a sheriff and mayor as the figures of authority of a town. My speed-reading understanding from the last trip to the internet is that a Celtic village would likely have a host — a person who is sort of like the closest thing to nobility a tiny village has — and that they were socially obligated take care of guests. I don’t like the word “host” as a position of authority no matter how historically accurate it may be, but I like the idea of it, so I change it the name of the position to be a hetman/hetwoman of a village and said that that’s Maureen. While I’m on it, I change the names to Celtic-sounding ones anyway, and switch the character to female because the module has no woman NPCs, and that seems wrong for a place named for its fertility.

Within minutes of your arrival, a tall, weathered woman with a bushy eyebrows enters the lodge and greets you. She carries herself with the quiet confidence of veteran warrior, but looks tired and rumpled.

So, we’re one paragraph into the module and I’ve rewritten all of it and added the following to the setting’s cannon about villages:

- They’re organized into hill forts with outlying farms/homesteads. Under attack, they get crowded because everyone in the community comes to the fort with all their animals.

- The person of authority is a hetman or hetwoman, who also acts as a host to any guests. The het can be a man or woman.

- The het and his/her family live in a lodge, probably along with any thralls and dependents. The lodge is also where they host guests, where outlying member of the community can stay if they’re under attack, and where important meetings or celebrations are held if they need everyone to gather together indoors.

Now, did my players notice the difference? Will they remember the details? Realistically, I’ll be lucky if they remember the name and a couple characters six levels from now. But I believe the accumulation of details leaves an impression in people’s minds. And if you have enough of the wrong details, their subconscious impression of the world will be vastly different than what you intended.

More importantly for me, it really helped me flesh out what the culture is like. I made bigger changes to the module later — replacing monsters, encounters, and sections of plot wholesale. But in those cases, it was only the adventure that was changed – it did not change how I saw the setting. It mostly that first paragraph, forcing me to think through the ambiance and social structure of the small village, that changed the world I had created.

I read an article recently that built a sort of skeleton town with basic stuff and then talked about how to customize it for your needs. But the problem is in the assumptions. They started by assuming that every fantasy town of course has a tavern. Except, of course, there’s no reason why they should.

I don’t know. I mean, we’ve all got this idea in our heads about what fantasy is like, and what are the necessary ingredients for it. And to build a setting, it’s easy to start with some platonic ideal of a generic fantasy and then add details on top, like a new pantheon or an exotic playable race or a secret organization. But I think it’s hard to make it feel real that way. It ends up a copy of a copy of a copy with a drawing on top to try to regain definition.

And sometimes when I read a book of someplace I’ve never been, the descriptions are somehow so rooted in luscious, concrete details that I swear I can smell the fruits the characters are eating before the author even describes them. And I want my players to feel like that — like the world I’m creating is a real place that they learn so well, they can tell me about it. And I think that to do that, I seriously need to check my assumptions about all the generic fantasy staples. Not just the big assumptions like gods and magic and dragons, but the little mundane things like torches and horses and taverns.

This is an impressive overhaul. I love that you were able to retain what worked and retool what didn’t fit so that, as a player, I would never have guessed you didn’t build the whole thing from scratch. (You’re giving away all your secrets!)

And with regard to players forgetting people, places, and things, I think a large part of that probably has something to do with fantasy-style names. How many people already complain that they can’t keep names — even ordinary, everyday, run-of-the-mill names — straight? Add in a bunch of sounds we’re not accustomed to, and it’s bound to be even worse. I would be curious how much easier NPCs named with some memorable characteristic would be, ex. Cuthaire Strong-Arm, Gwideon the Fox, Orrubos of the Red Eye. I probably wouldn’t remember Cuthaire, Gwideon, or Orrubos, but it’s possible I’d refer to them by that more easily remembered characteristic.

Likewise, I think there is very little chance that I won’t remember the name Fertile Crossing, while the name of the city of Amanuenis has basically 0 chance of being recalled in three sessions.

Does she like to tango? Has she ever pouted her lips, and called you pookie? Is she… less het… than her title lets on? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D0QfCIQgD94

Seriously, though, I love how much consideration you put into the political structure. I continue to pray that you have been secretly publishing fiction under a pen name.